[adinserter block=”3″]

As told to Nicole Audrey Spector

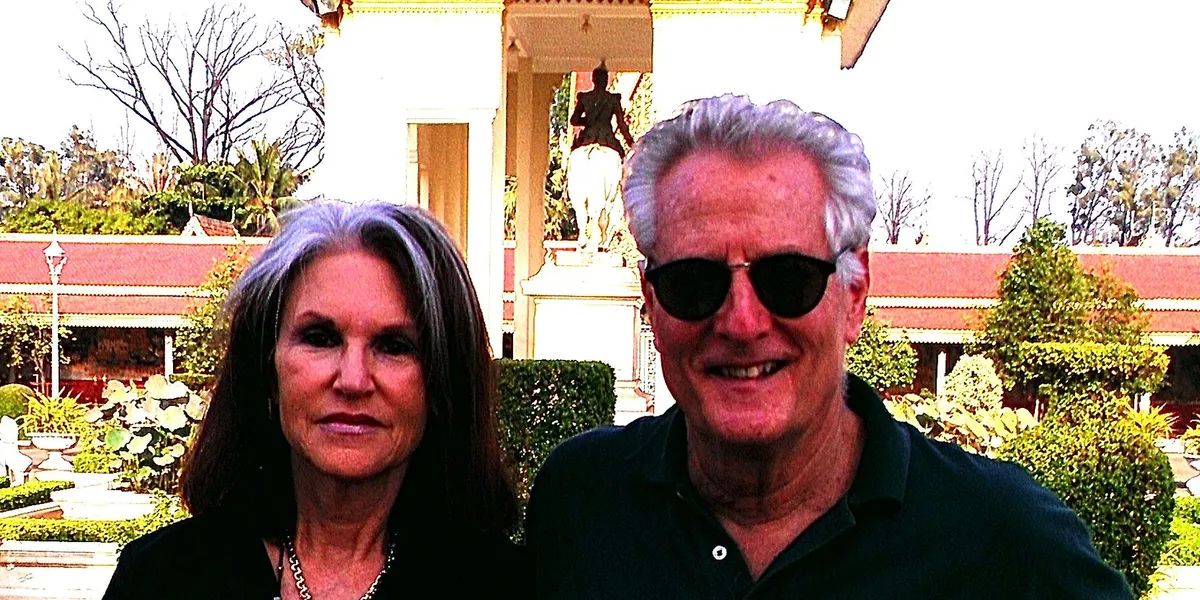

I knew my husband, Bob, had Alzheimer’s disease before anyone else did, including Bob. He was only 65 years old, but he had some of the telltale symptoms, including forgetfulness and absentmindedness, which were highly unusual for him. Bob was whip smart and incredibly high-functioning, a former journalist. But the bills, which he handled, and which we had the means to pay, were starting to pile up. Something was wrong. And I, having studied Alzheimer’s in my career as a women’s health researcher, was all too aware of how the disease can strike.

Bob went to see a neurologist and was told everything was fine — that his symptoms were just a normal part of aging. But I knew the neurologist was wrong.

Around this time, I happened to be putting on a women’s health panel featuring a physician who was an expert on Alzheimer’s. I set up an appointment for Bob with this doctor, and we quickly had the dreaded but accurate diagnosis: Alzheimer’s disease.

For a few years after the diagnosis, Bob was OK. Not great, but well enough to travel with me and live a somewhat normal life, although not independently — I was always by his side. But he deteriorated as one with Alzheimer’s always does, and eventually it came time to move him into a memory care facility — a difficult decision if ever there was one, but one that I felt was best for Bob’s health and general well-being.

Bob stayed in the facility for awhile, but I wasn’t happy with his quality of life there. Ultimately, I decided that he would be best off at home, with me, and a train of ‘round-the-clock caregivers.

It may have been my husband’s body in the house with me, but the man in the house was not my husband. Bob was long gone by then. This man was but a hollowed out, cracked shell of my husband. He didn’t even really look like Bob. Not truly. The intellectual gleam in his eye, the glimmer of a sturdy, familiar mind, was erased. The strapping smile, the confident posture, the ability to be effortlessly laid back … all deleted like some old copy in one of his stories that never made it to press.

I occupied the upstairs of the four-bedroom house and Bob and the caregivers took the downstairs area. Though I was never alone, and I had plenty to occupy myself between work and my social life, there was a loneliness to my days and a gnawing guilt combined with a kind of grief in reverse. Bob was still alive, but I missed him, and I also at times resented the helpless, crazed person he’d become. And then I felt bad about that because, of course, he was an innocent victim in all of this.

I lived in a state of constant agony watching Bob’s descent, but there was one thing that helped buoy me, and I didn’t even really know it at the time.

I’ve always loved to paint and found myself profoundly drawn to the canvas during Bob’s decline. Painting gave me a sense of focus and drive that had nothing to do with my work or my personal life or Bob. It was entirely creative and self-motivated and gave me tunnel vision in the best sense of the term. Painting blocked out the rest of the world and provided me with a launchpad for the mornings. Often I’d wake up with the first thing on my mind being how I’d continue the painting I left off the day before.

A painting by Phyllis Greenberger

While Bob was dying (because really, that’s what was happening all during those 15 brutal years that he was slipping away), I spent much of my free time absorbed in making art. Since Bob passed in March 2022, I’ve continued painting and have even sold some of my work.

Right now, I’m in a bit of a rut with painting and with my grief. Work is good. Friends are good. I have a new book coming out and other exciting things on the horizon. I have things to look forward to; I know this. But my best friend, who happened to be my husband of 50 years, is dead. He died a horrible death, and I watched every tormented second of it. There’s no way to sugarcoat that, or the fact that the last dozen or so years of our lives together were riddled with the trauma, the despair and the cruel madness that Alzheimer’s brings.

There’s a painting I started in my kitchen. It’s the one that I’m in a rut with. I can’t miss it because I cross its path everyday. I don’t like it as it is, and I know I need to change it, but I don’t know what to do with it. One of these days I’ll throw black paint over it and start over. That’s the thing about me. I never leave things unfinished. And if I don’t like something, I always fix it so that I do. It’s just a matter of getting to the place where I can start again. It has to come to me. I know it will.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

[adinserter block=”3″]

Credit : Source Post